Ten generations of Canadian heritage

by Tom Thiévin

B7 C8 D1

Sadly, Tom Thievin succumbed to stomach cancer in 2007. His brilliant efforts at gathering our Côté history live on in this article.

|

|

Tom Thiévin and all D-generation

offspring of

Louis Auguste Thiévin are great-great-great-great-

great-great-great-great-great-great grandchildren

of Jean Côté. Louis's wife was Marie-Louise Côté

from Olga, North Dakota. |

I have but one regret: I think my father would have been fascinated by this information. It is completely possible that some of his buddies in the RCAF Alouette Squadron in World War II were distant cousins, and he would never have known.

Just as my father

did with similar projects and similar intentions, I started this as a little research that would help my progeny know their ancestry. I wanted a reasonably

accurate summary of one side of our family history. The material

before me was extensive, based on information available at the

time. When I finally began to write, if I followed any lead, it

would be the book The French Quarter by Don Graham. (No

relation to my patient wife, I think.)

Alas, things have changed. A few years ago a handful of people

shared information openly and freely. A loose network of relatives,

old papers, and non-related historians worked in a friendly way

to solve many genealogical and historical riddles. When someone

suggested a date that another thought was incorrect, a friendly

discussion ensued: "Say, Joe, if such-and-such happened on such-and-such

date over here, then this date would have to be after that. What

do you think?" It was friendly, and free, and fun.

But nowadays people are selling information, correct or otherwise,

thinking that if they discover something, they should be financially

rewarded. Some outright bash others if they think something is

incorrect. Some get upset because they feel they should get credit

for information they think they alone discovered, even when sometimes

their 'discovery' is the worst-kept secret in town.

I don't claim to have discovered any of the following, nor am

I selling it. Much of it is well-established history. The rest

represents information gathered over several years from hundreds

of sources, many of them verbal, and I'm sorry to say, forgotten.

I cannot properly credit each person involved because sometimes

at a reunion, a relative might say, "I don't know where

|

I

got this. It's been in the family attic for years

and I'd hate to see it lost. If this interests you, it's yours."

In a friendlier world, I think people would understand that. Now

I hesitate to use names in credits simply because I don't want

their good intentions subjected to ridicule and bashing over inconsequentials.

I don't know how many Jeans, Abrahams, and Annes are going to

turn up over the next few years. My hope is that friendly and

free information will be exchanged and that the 'fun' part of

this will continue. And please, if you read something here that

you know to be incorrect, email me before you do a slash, bash,

and burn on a message board. I'm not trying to spread my doctrine

or theory of life. I am trying to report the story and its associated

historical aspects as accurately as I can.

I have one last rant: Please do not email me if you have 'discovered'

a Côté shield, badge, medal, or banner on the internet or elsewhere.

My morals do not allow me to participate in something that some

businesses at fairs and malls seem to have no problem with, and

that is the practice of selling shield patterns and family-name

histories prevalent in English culture. These businesses might

make you feel warm and cosy about family honour, bravery, and

whatever else. But there is enough information available to show

that for French peasants, these items did not exist. I'll happily

change my stand if there is real proof otherwise.

Many thanks to all who have supplied information, historical and

genealogical, including criticisms. It's all appreciated. Your

interest in the Côté story will go a long way toward helping others

if we can keep our search friendly, free, and fun. |

CONTENTS (Click to advance to a chapter)

Introduction

This article is a survey of our Côté genealogy. There are as a conservative

estimate about 50,000 — perhaps even as many as 100,000 — Côtés or

persons in North America linked to the bloodline, and most, if not

all of them have Jean Côté, who arrived in North America in 1634,

as their original ancestor. In all of French Canada, only the Trembley

family is larger. My work was simplified by the quests of many other

Côté researchers who preceded me in exploring the rich history that

is the subject here.

Since Côtés are so interleaved with early Canada and Québec, some

history, or perhaps my version of it, is proffered to better state

the facts. I could only skim the surface of this complex heritage.

But there's much more to consider, and I invite you to delve deeper.

Lastly, a note on the finality of information that follows: My research

came primarily from the internet and from sources available in Alberta,

so the work is not exhaustive. If you study church records in the

Lotbiniere municipality in Québec or look up military records, French

naval records, and other documents from the 1600s, you'll immediately

expand on my work. These sources weren't available to me. While there

was every attempt to ensure accuracy, history will probably indicate

some errors in what I've reported below.

The spelling of the name Côté

The direct French translation of côté is "side". The French

translation of côte (without the grave on the e) is

"coast" — not altogether different in meaning from "side". In an interesting

linguistic similarity, the latin costa also means "coast",

as in Costa Rica, meaning "rich coast".

According to Appendix 1, a Jean Coste was aboard the ship Le St-Jean that arrived in Québec in 1634. But this signature belonging

to Jean Côté ...

|

... at http://web.ionsys.com/~microart/jean.htm clearly shows his name

as Jean Coste. Like many French Canadian family names, it appears

two basic spellings exist; one an Old World spelling, Coste, and the other a New World spelling, Côté.

Like most other Côté researchers, I've used the spelling Côté throughout. This was

an arbitrary choice since there are actually many spellings. Côté was chosen simply because it was more frequently used by the family

after the first generation.

Lending to the chaos was the French Canadian use of 'dit' or 'nick'

names. The dit name was actually more, sometimes a lot more, than

a nickname. Often the dit name was the more common name and was substituted

on legal documents and other records without much regard for spelling.

For example, when soldiers of that era joined the militia, they were

induced into their regiment with a hazing and usually given a 'dit'

that often had no cognitive meaning. Often the dit name stuck and

occasionally became the family name.

In the case of Jean Côté, it appears he was known as "Jean Côté, dit

Costé". The latter name appears to be the one most used by generations

before Jean and by the first generation, that is, Jean's children.

There is evidence that the name Cottez was also used. Sometimes

too, Jean is spelled Jehan. When translations from other

languages are used, all phonetic possibilities have to be considered.

This is interesting in that as a typical French farm labourer and

peasant of that time, it's highly improbable that Jean Côté was educated

or knew how to read or write. The signature mentioned above might

well have been made on his behalf and with his acknowledgment. At

best, it might have been the only thing he could write. The exact

spelling was probably not important for the time and status of those

involved.

Other names that appear in various records that refer to members of

this family lineage are Coté, Côte, Cote, Cotoe, Couty, Cotey, Caudy,

Cauta, Caute, Cete, Costey, Costez, Costé, Cota, Cotta, Cotte, Cottez,

Coty, Gaudy, Lefrise, Side and Sides. (Remember that Côté translates

as "side" in English). Research suggests that Cody and Cole belong

on the list, but since they are also common English names, sorting

them from the French could be an impossible challenge. Certainly the

earliest property records in Québec suggest that the name Costé was more common in the first generations.

Careful choice of names was applied more among the landowning upper

class and for legal documents of the middle class. If the research

from France stands, Jean Côté was from the working peasant class and

not a landowner in Europe, so it's also unlikely that this spelling

is consistent in Europe. For that reason and because little information

has been found to indicate service in the military, it's also unlikely

that a family crest or shield was commissioned, although one appears

at one Côté site on the internet.

Finally, there's a discussion site on the internet where some Côtés

have reported various pronunciations of their name. These include

"Coat" as in goat, "Cotay" as in no way, "Cotee" as

in goatee, and so on.

Early Canadian history

This is significant since it defines the reason we're here at all. An Italian, Giovanni Caboto (sailing for England as John Cabot) claimed

Newfoundland for England in 1497, and this led to exploitation of

the Grand Banks fish stocks off the east coast. Then in the 1530s,

the Jacques Cartier explorations claimed the St. Lawrence River and

the present Maritimes area for France. Both Natives and Europeans

recognized that fur trade was possible, and so trading began, something

that the Natives regarded as common, for things the Europeans had:

tools, metal wares, and later, guns and alcohol.

Present-day researcher, Pierre Côté, to whom much gratitude is due,

discovered various references to suggest that Costes were involved

in fishing activities off Newfoundland in the 1570s. (Pierre is now

trying to find verifiable lineage to our Jean Coste.)

But back to the history: A French commoner, Samuel de Champlain, became

an expert in exploration and cartography and was convinced that the

area had great potential. To that end, he set out to get commercial

and governmental sponsorship, to inhabit the area with French people,

and to begin land surveys. His first fort, Port Royal in Nova Scotia,

failed due to severe winters and a lack of farming and survival skills

needed by the new French inhabitants. For many the adventure ended

in starvation. An interesting thought: The Pacific weather disturbance

now known as El Niño occurred in those years and may well have played

a role in the unusually cold and long winters.

After piquing the interest of a commercial group in France, Champlain

began work on his second and most lasting colony called Québec or Kebec, which was the Native word for the place where the St. Lawrence River narrows.

Champlain's work in New France, mapping and setting up treaties with

the native aboriginals, organizing settlers, and generating interest

and sponsorship of the colony in Old France probably made him the

best ambassador Canada has ever had. He also learned the various aboriginal tribal political systems and created many alliances and trading

agreements whose importance was realized only years later, often at

great cost.

Some interesting dates in Europe during this era:

1585

- Raleigh establishes the first colony in the North America

1597 - Godson shows a flushing toilet to the Queen

1605 - King James 1st has scholars start writing the King

James version of the Bible, while referring to his manservant

George Villiers as '... my sweet child and wife, ... and grant

that ye may ever be a comfort to your dear dad and husband.' **

1609 - The song Three Blind Mice is published

1612 - The Dutch establish a trading post on Manhattan Island,

and King James I (same guy as above who has his name on the

King James Version of the Bible) holds a lottery to finance

the creation of Jamestown in the New World

1620 - The Pilgrims arrive aboard the Mayflower

1627 - France tries to ban duelling

1628 - Half the population of Lyons dies due to the Black

Plague.

** See Marriage Relationships in Tudor Political Drama by Michael A. Winkelman or simply Google this for more information.

Interesting

dates in New France and Québec:

1607 - Champlain's settlement at Port Royal fails

1608 - Champlain sets up a new settlement at Québec

1609 - Champlain assists the Montagnais tribe of Indians who

were at war with the Iroquois

1615 - The first missionaries arrive at Québec

1617 - Louis Hebert and family arrive. (Herbert is often credited

being Canada's first farmer when, in fact, the Indians were

farming for centuries before his arrival.)

Later in the 1620s, Dr. Robert Giffard from Mortagne in the

Province of Perche in France visited and became interested

in the area.

|

In 1627 fewer than a hundred Europeans lived at Québec. (Unless otherwise stated, "Québec" alone means Québec City.) That year

the 'Compangie des Cent-Associés' was created to capitalize on the

growing fur trade and colonize and manage the area. In essence, Québec

became the property of this company.

In 1628 the company sent 400 settlers, but they were met at the mouth

of the St. Lawrence by the Kirkes brothers who had claimed the area

for England. The Kirkes blockaded the St. Lawrence, sacked Québec,

and shipped settlers home until 1632 when the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye returned the area to France. In early 1633 there remained six families

and five aboriginal translators living in what was now dubbed "New

France".

The first problem was attracting settlers to live somewhere with little

hope of making a profit and a climate far colder than France. Recruiting

fur traders was relatively easy, but farmers were another matter.

France, even northern France, had a warmer climate and a longer growing

season. Farming without crops that could endure this climate was a

challenge.

France also had a well-entrenched class system, essentially a feudal

state, and landowners, the upper class and the nobility, had little-to-no

interest in relocating to New France. Black flies and cold winters

were enough to keep anyone with privilege or entitlement well away.

For them it was preferable to risk the Black Plague then making its

way through Europe. Added to this were reports of Indian hostility, so recruiting

farmers and labourers who might relocate to this inhospitable land would

be very difficult.

The start of the seigneurity system

The initial proposal by Cardinal Richelieu, agreed to by the king

of France, was to grant rights to full exploitation of the area to

the Compangie des Cent-Associés. This company realized that unless

the area was settled, there was little hope to profit over the long

term, and so they allowed the granting of land parcels to those who

could clear and develop them. And so started the seigneurity based

on the fiefdoms common in France, a culture understood by both those

granted land and those who agreed to work to clear it. See www.cam.org/~qfhs/FAQ_land.html.

Based on the medieval practice of 'no land without its lord', the

plan intended to make Québec and New France hospitable or at least

suited to habitation. In Québec this was just a narrow strip of land

touching the river's edge and inland several miles. Entrepreneurs

would develop parcels by employing peasants as labourers.

The lord of the seigneurity was the seigneur (French for 'lord') who

had absolute control over his domain, including matters of education,

policing, medical, marriage, and food and shelter for his labourers.

He built and maintained flour mills and other required public buildings.

Most seigneurs drafted tenuous legal contracts that, when read between

the lines, favoured themselves. For his investment, a seigneur collected

rent and whatever else he could extract from his tenants. All of this

was supposedly done as homage for the king and God.

In the end, labourers who survived the ordeal would have the blood

of some of the most determined and hardy people to have visited any

part of this planet. Those who failed returned to France with little.

That is, if disease, the Indians, or some accident didn't kill them

first.

It should surprise no one that most seigneurs were motivated more

by greed than reverence. And since most early settlements were not

very successful, they found themselves doing all they could to keep

their tenants. There would be many verbal agreements, land and animal

swaps, legal entanglements, and law suits.

Many French Canadian families tell this story.

Recruiting settlers for New France

The French navy had a regulation that required that every ship have

a doctor on board, and as a result, a Dr. Robert Giffard arrived in

New France with the first wave of French migrants. He visited the

old settlement at Port Royal and at Québec, and he was among those

sent back to France by the English Kirkes. He was, however, quite

impressed with the area, and when the Company of a Hundred Associates

came calling in 1633, he returned to New France to create a seigneurity.

Like any seigneur, Giffard needed farm workers. These he recruited

from his home region, Mortagne and Tourouvre in Perche. He already

knew what it would be like and what kind of people were needed. His

settlers would have never experienced severe winters, hostile aboriginals,

isolation, near starvation, back-breaking work, wilderness, and billions

of black flies. They must not only survive all of that, but they would

need to grow in number, prosper, and create a new home and country

if Giffard's aspirations were to bear fruit.

From the Perche area of Normandy, Jean Côté, dit Costé accepted an

offer by a man now considered to be the first seigneur in Québec:

Robert Giffard. While the legal document that would bind Côté to his

seigneur hasn't been found, we presume that it stipulated that he

work for Giffard for a period in exchange for his passage. The contractual

duration is also unknown, but agreements of that era usually stated

five years after which a cow or other livestock, some land, or whatever

else, was awarded to the labourer.

Côté was among the first Normans recruited, along with Jean Guyon,

Marin and Gaspard Boucher, Sébastien Dodier, Zacharie Cloutier, Pierre

Paradis, and Pierre Maheu, Guillaume Isabel, the Desportes family

and a few others. Generally, seigneurs knew that to have permanent

settlers, they must attract families or tenants who would start families.

Jean Côté, being single, was perhaps not an ideal candidate, but he

likely had desire and a durability that interested Giffard. Many more

Normans would arrive later.

There are now very good historical information websites developing

such as www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/paris/canadafrance/percheemigration-e.asp.

This one nicely explains Dr. Giffard's exploits.

Our ancestral beginnings

in "New France"

As previously mentioned, life in the old country in the 1600s was difficult,

especially for peasant classes. A peasant was essentially devoid of

rights. A peasant who wanted a better life could try to obtain a cow,

a pig, or some chickens. It was possible to do this by careful trading,

and eventually he might gain status, possibly even some land. But

the chance was very small. Even if an animal was acquired, the army

might pass through and take it. And there were taxes. Peasants, owning

very little, had few taxes to pay, but any tax for those with little

or no income was an extreme hardship.

France in the 1600s had no sewer systems, and the filth of animal

and human wastes and consequent threat of disease was everywhere.

While finding suitable recruits for the New World might have been

difficult, it was probably easy to fill boats with French peasants

looking for a better life, especially if a cow or some other asset

was part of the promise.

Our Côté ancestry began in New France with Jean's contract with Seigneur

Giffard, a woman named Anne Martin, and a free voyage. Jean landed

at Beauport (see Appendix 1 below), now a subdivision of Québec City,

to begin a new life. A website at www.genealogie.org/famille/belanger/FrancoisImmigrant.html provides insight to the Québec community and other aspects of life

at that time.

Guesses could be based on what is known about the ships of those days

and prevailing circumstances. If the television show A Scattering

of Seeds - The Creation of Canada is of interest, its website

at www.whitepinepictures.com/seeds is worth a visit. Another site at www.geocities.com/Heartland/Ranch/6210/01_navires_pre_1666/E1navires.html states the number of ships and their captains for those early years.

|

| Window

glass was not generally available until a process was developed

in France in 1688. Homes of those days had no windows, and if

building ideas from the old country were employed, most homes

would have only had openings covered with an oiled, translucent

paper that could be shuttered in the winter. The movie Blackrobe, directed by John Lantos, written by Brian Moore, is set in Québec in 1634. While it's mainly about the spirituality of the Jesuits and the Natives, it also portrays many aspects of life in that

area at that time. The roles of workers, the clergy, and even

Champlain seem carefully considered and portrayed. The

window used by Champlain appears to be oiled paper, which would

have been correct for the time. |

The site at www.geocities.com/

Heartland/Ranch/6210/ which is the home page of the site above

contains good data and links. (Yes, I have noticed that the plaque

on the memorial to Louis Hebert states that Jean Côté arrived in 1635.)

The search engine at this site links to the www.ancestry.com site, and this might be useful to US-based Côtés. There are also considerable

errors here. But given that this site is hosted by an American-based

protestant church, it's likely that our Jean, who was a faithful

and loyal Roman Catholic who paid homage to his seigneur and to his

God, wouldn't really care.

It appears that in 1633 the dozen or so people at Québec saw their

numbers increase to a couple hundred with arrival of three or more

ships. In 1634, if the information in Appendix 1 is correct, Jean

sailed on a ship that was part of a flotilla, of sorts, of five or

six ships. His vessel could well have carried 75 souls comprised of

families, soldiers, and missionaries and basic tools, supplies, and

animals for farming and articles for fur trading. Most sailings were

in summer months, and their arrival in Québec would have significantly

boosted the population to 500 or more. Vessels would have then collected

furs for the return voyage. Generally ships of that era were supplied

by the French navy, which is why searches at the French naval archives

might be fruitful.

Jean Côté's origin

Until recently, very little was known of either the early life of

Jean or 'Jehan' Côté, dit Costé, or his precedents in France. Thanks

to work by Pierre and Jean-Guy Côté, there is evidence suggesting

who his parents and grandparents were. Dozens of websites state the

basics of Jean's marriage to Anne. Many of them differ. I don't think

I could be criticized too harshly for suggesting that he was born

in about 1604, son of Abraham and Francoise Loisel. (Much genealogical

data from these years poses problems with similar names, improbable

dates, and so on, especially where it involves peasants and the French

lower working class, so some inaccuracies are plausible.)

Appendix 2 below contains information from Jean-Guy Côté. It's definitely

interesting, however, questions arise. One is that it's in English

and it might have suffered in the translation. Another is that it

refers to the Côté spelling, and this might not have been the name

Jean and his predecessors used. Another problem is that there aren't

yet any links to the persons indicated. Still, the information shouldn't

be ignored since it could disprove some of our thinking.

"It is most likely that (Jean Côté) came

from Perche, but he is one of the rare settlers about whom tireless

researchers, such as Pierre Montagne and his wife, have discovered

nothing in the archives of this French province. Without a doubt,

it is for this reason that they do not mention him in the Percheron

Cahiers, nor in Tourouvre et les Juchereau."

I have found the essence of this paragraph in several sources on the

internet.

There is also a good chance that Côté came from the Dieppe area. Information

is surfacing to suggest Coste namesakes were involved in the fishing

junkets to the Grand Banks.

Jean Côté's peasant background, marital status at the time of his

departure from France, and apparent absence of military service certainly

gives rise to another more sinister speculation: that he was on the

lam. I believe it would be wrong to discount this possibility, and

it creates yet another fascinating wrinkle in the mystery behind this

intriguing man whose genes are now replete in tens of thousands of

North Americans.

Our original Côté matriarch

Jean Côté's blood does not run in our veins without worthy consideration

of the woman he would marry in the New World and whose genetic blueprint

we equally carry. So for a moment, we turn back to France and the

ancestors of Anne Martin, specifically her grandparents Galleran Martin

and his wife, Isabella Côté. Yes, the Côté name appears here too,

and I will explain:

It's doubtful that this was the grandmother's true family name. Since

Côté also means "side", she simply may have been "at the side" of

Galleran according to nomenclature in ancient cultures. Galleran was

devoted to the cause of Mary Queen of Scots, but it's unknown whether

he was a Scot living in France or a Frenchman spending time in Scotland.

Currently it's believed that Galleran and Isabella were from Scotland.

Galleran was involved in a plot to free Queen Mary from the English.

The plot failed. History knows well that Mary was beheaded. Galleran

fled to France with his family.

Galleran's son, Abraham Martin, was born in Scotland in 1587. Abraham

arrived in New France (Canada) on the sailboat LeSallemandie at Tadoussac

on August 30, 1620. His wife was Marguerite Langlois, whose sister

gave birth to the first European born in Canada. After the takeover

of Québec by the Kirkes, Abraham was sent back to France with hundreds

of others, as stated above. But in 1633 he returned to Québec with

his family which now included a daughter named Anne. He worked as

a river pilot, ploughman, and fisherman. Abraham is often noted as

Abraham Martin dit l'Ecossais, meaning Abraham the Scot.

But possibly there were two Anne Martins. One was a kid sister to

Abraham, born about 1617; the other was Abraham's daughter, born on

March 23, 1621. I raise this since either one could be the Anne Martin

who ultimately married Jean Côté . Both were born in Perche Province

in France. The assumption is that Abraham married Marguerite Langlois

in France on Oct 24, 1621, leaving Anne to have been born before the

marriage in both cases.

Anne, Abraham's sister, was born in 1617 and would have been 28 years

junior to Abraham. Her mother would have been about 50 at the time

of her birth. She could have met Jean while in France and then travelled

on one of several ships that arrived from France in 1635, and at the

time she would have been about 18. She might also have arrived as

a guest of her brother with a view to see what might develop with

Jean.

Anne, Abraham's daughter, was born in 1621 and would have been 15

at the time of her arrival from France and her marriage to Jean. While

this is possibly more credible than the first scenario, it conflicts

with data that suggests Abraham and Marguerite had another Anne born

in 1645. I will hold to the notion that the Anne who married Jean

Côté was Abraham's daughter, unless other data arises to the contrary.

A message I received, possibly from Pierre Côté, indicates that records

were lost in a fire, and the year 1640 comes to mind. If so, much

critical information about Canada's first settlers will never be known.

Côté generations since arrival in North America in 1634

|

The first generation |

| Jean Côté and Anne Martin |

Logically, though it's not verified, Jean Côté and Anne Martin, based on

the birth of their first child, were involved in a relationship by January

or February 1635. The child, Louis, was born on October 25, 1635,

and they were married a few weeks later by the missionary Jesuit Charles

Lalemant on November 17, 1635 at Giffard's home, with Giffard being

their witness and sponsor.

Jean was a cultivateur meaning a farmer, farm labourer, or gardener.

Since Giffard himself had nearly starved in this new climate a few

years earlier, Côté and others like him were critical to the success

of his seigneurity. Jean Côté worked as a fief or tenant, clearing

land and farming for Giffard at Beauport. After probably five years,

he was given an 'arpent', which is about an acre of land. He may have

also received a cow, since this was a common payment for services.

Champlain died a few months later at Christmas, and virtually the

whole settlement at Québec attended his funeral. Doubtless, our Jean

and his wife were there too. One only wonders what they and their

fellow settlers were thinking. Surely they pondered their future since

Champlain had been their guide, their protector, and their sponsor.

He had arranged peace with the aboriginals and had battled tirelessly

on both sides of the Atlantic for everything that Québec had become.

This was a dreary and foreboding time at the settlement.

Gradually it was evident that land seigneurities would never rival

the great fortunes created from fur trading, and France's interest

in colonization began to wane. It also became clear that the settlement

had much more land than prospects for creating seigneurities. Those

who came as peasant labourers realized that they too could have land,

and it wasn't long before seigneurities were also granted to peasants

and labourers as freely as they were to France's elite.

In August 27 1636, governor Huault de Montmagny, who had succeeded

Champlain, gave Jean Côté an arpent facing the river, but it was hardly

sufficient to raise a family. The children who followed were:

Louis, 1635-1669

Simone, 1637-before 1698

Martin, 1639-1710

Mathieu, 1642-1696 |

Jean Baptist, 1644-1722

Jean Noel, 1646-1701 (our branch)

Marie, 1648 (died at 2 weeks old)

Louise, 1650-1696 |

Very likely all were

born at their home in Beauport. For Jean's descendants at least, this

was the first generation of Canadian born Côtés.

Some of the information following is commonly known. Who actually

"discovered" it is hard to determine. Some of it is also covered again

in Appendix 1.

A neighbour and relative of Jean's (the brother of his mother-in-law),

pioneer Noël Langlois, owned 300 acres that Giffard ceded to him in

his seigneury of Beauport in 1637, and in return for Jean and family

living close by, Langlois provided some homestead land for Jean. In

1641, Langlois and Jean made a contract with the Company of New France

for the supply of 500 bundles of hay at the price of 80 livres, the

currency at the time. Jean built his house, and in 1645 Lord Giffard

granted him ownership of the ground that he occupied; about three

acres. This land became the subject of a dispute over theie verbal

agreement. In the end, the act of generosity caused more problems

than it solved.

Jean Côté became the owner of a house situated near the present corner

of the rue Trésor (Trésor Street) and the rue Baude (Baude Street)

in modern Québec City. Today this is an alley where artists display

their creations for tourists. The house was on a plot of land with

150 feet of frontage and 60 feet in depth. On 15 November 1649, Côté

offered it as dowry for his eldest daughter Simone when she married

Pierre Soumande. On 7 November 1655, Soumande sold this house to Jacques

Boessel for 350 livres. Côté also owned a piece of land between la

Grande-Allée and the river in what was then the outskirts of Québec.

The act was ratified on 5 April 1639 for the land Governor Montmagny

had given him on 27 August 1636.

The practice of passing the homestead to the oldest male doesn't appear

to have occurred in this case. Jean Noël was three when his older

sister married Soumande, and apparently the boys all had to look elsewhere

for their homestead.

Just off Québec City in St. Lawrence River is a large island, about

21 by 5 miles in size. Even Jacques Cartier remarked at its beauty,

eventually naming Ìsle d'Orleans after a friend. In 1651, the residents

of this island were granted fiefs by the governor, and it became possible

for commoners to take up land there. (Check www.lachances.net for a very nice website made by the Lachance family on this island.)

Probably due to availability, all the Côté boys took up acreages there,

and from there the Côté bloodline began its movement throughout North

America.

It's interesting that ancestors of ex-prime minister Jean Chretien, singer Celine Dion, and

many other famous French Canadians also came from this island.

The aboriginals

There were essentially four nations of aboriginal peoples in the area.

The Algonquin and the Montagnais were traders, peaceful and quite

nomadic. Their territory was mostly north and northeast in the backwoods

of modern Québec and Labrador. The Hurons were south and east in the

area now known as the Eastern Townships. This is now cultivated Québec,

Maine, and New Brunswick. They were somewhat agricultural, peaceful,

and also nomadic.

The Hurons were often attacked by bands within the various Iroquois

nations and the Mi'cmaq, and a threat to Huron populations existed.

By 1639 their numbers had been halved by European diseases and wars

with other more aggressive aboriginals. There is interesting historical data at

www.dickshovel.com/mic.html.

In 1641 a priest working with the Hurons named Jean Brebeuf wrote The Huron Carol.

Then in 1649 the Iroquois tortured and killed

him and Lalement (not the one who performed the marriage ceremony

for our Jean and Anne in 1635). This was a time when the probability

of capture and harrassment or killing by the aboriginals was quite

high, especially for those who were out of the range of safety of

their homes. It's surprising that there wasn't a huge outcry or a

large-scale retribution over Lalement's death.

In 1660-61, the Iroquois were again at war throughout the area attacking

Montreal and even pillaging Ìsle d'Orleans. These wars totally decimated

the Hurons, and since fur trading depended largely on them as middlemen,

it began to subside.

Jean Côté died in Québec on March 27, 1661. According to Appendix

1, he is buried in the church at Notre Dame Church in Québec City,

although this is disputed.

In 1663, King Louis XIV made New France a crown colony with Québec

becoming a royal province, and royal governors or intendants would

replace private commercial interests in governing Québec. In 1660-70,

black or bubonic plague was taking its toll in Austria, Italy, and

southern France.

Populating French Canada

In 1665, France sent Jean Talon, "the Great Intendant", to take over

as head of the colony, and the first challenge he faced was to increase

the population. In 1666, Canada's first census revealed a population

of 3,215, and by 1672 it was 7,000. Since it was now formally a colony,

the French crown paid for the passage of thousands of settlers, even

disbanding the Carigan-Salières regiment and forcing them to stay.

Proably the best accounting of the soldiers is at this website: Carignan-Salières Regiment Officers and Soldiers.

The ratio of men to women was 6:1 in 1666, that is, about 2,800 males

and just 400 females.

France had sent the Carigan-Salières Regiment, a thousand or so soldiers,

to protect its developing colony. During this time, the arrival of Filles

de Roi (daughters of the king) became a famous historical

event. Prompted by Talon, the king sent females to the colonies to

promote marriage with soldiers and other marriageable males. Between

1663 and 1673, roughly 800 women from 12 to 40 years of age, some from orphanages,

and others from poorer families

in France's western provinces, were sent across the Atlantic. An excellent list of

those who married is at www.prdh-igd.com/en/les-filles-du-roi.

|

|

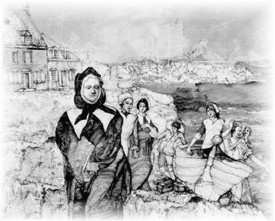

No fewer than 18 of our Côté ancestors were among the Filles du Roi — "daughters of the king" brought to Canada in the 1600s to boost

Québec's population.

Painting: "Arrival of the Filles du Roi at the Maison Saint-Gabriel" by David Mackie, depicting Sister Bourgeoys meeting some filles upon their landing. |

Despite rumours that they were poverty-stricken street people,

in reality they had rudimentary educations and were required to qualify

before they received a small dowry and passage to the new world. And despite unkind things

that have been said about the integrity of the Filles du Roi, within a few months

of their arrival, most had indeed married, and eventually nearly all married.

While calling them the king's daughters might have added some dignity to the affair,

in fact to Talon and to Québec, they might have been the king's crown

jewels for the demographic benefit they brought to New France. If not immediately,

these brave women would understand that their new lives came with serious demands

— nursing, child-rearing, survival basics, and an important role in building the new

frontier. Their contributions are still beyond measurement.

It was not what the Filles du Roi were or what they possessed,

but rather what they were not. They were not privileged ladies of

the courts or from upper/middle class backgrounds. They intimately

knew the realities of hardship, of hard work, and of being in a difficult environment.

The dowries provided by the king injected valuable economic assistance

at the family level. Their arrival and presence was exactly what Québec

needed, and a baby boom of unprecedented proportion followed. In 10

years, by 1677, the population more than doubled. Fifteen years after

Canada's first census, the genders were about even in number, and

the Filles de Roi were as close to a perfect solution to a

problem as there ever was in history.

| The bloodlines of our Filles du Roi are not unique to Canadians. Fast-forward a few centuries, and Hillary Clinton, Madonna, Angelina Jolie, and probably many others are among

notable North Americans who claim ancestry from the brave Filles du Roi of Québec. |

Since their numbers amounted to over 10 per cent of the population,

the bloodlines of the Filles du Roi quickly permeated the entire French Canadian population

in the area. There are very few unfortunate French Canadians from

the Québec era who aren't related to at least one Fille de Roi or soldier from the Carigan-Salières regiment. As mentioned in Appendix

1, one of Jean Côté's sons married a Fille de Roi. Hockey fans might

be interested that Guy Lafleur and many other famous Canadian hockey players are descendants

of the soldiers of the Carigan-Salières Regiment.

Within a generation, Québec transgressed from a wilderness trading

outpost to a somewhat decent, family-oriented society and culture.

This marked the beginning of a major change in the makeup of French

Europeans in Québec. From this period on, approximately a third were

Normans from rural areas of France, and the rest were from the urban

areas, split up such that half were the military and filles de

roi, and the others were missionary, governmental, and administrative

people.

If the Filles de Roi event wasn't enough to elevate Talon's

reputation, other aggressive steps to encourage population growth

surely helped. In 1669 he issued a royal decree that stated that

girls were to be married by age 16 and boys by age 20. Those who complied

were given 20 livres. And to make sure parents were productive, they

were given a pension of sorts of 300 livres per year for having 10

or more children (children who became priests or nuns didn't count!),

and those who had 12 or more got 400 livres annually.

The birth rate rose to over four times that of today. With Talon's

encouragement, a culture developed of early marriage, large families,

and quick remarriage upon the death of a spouse. The birth rate, coupled

with free passage to New France from Europe, sent numbers soaring,

and thus it took little time to populate the land with the next generation.

During this period, Ìsle d'Orleans quickly became completely inhabited.

Each succeeding generation would have to look elsewhere for land.

The changing class structure

In 1670, Hudson's Bay Company was granted a charter from the king

of England to trade fur in the Hudson's Bay area. This started another

round of fur-trading wars and caused many skirmishes among traders,

aboriginal middlemen, and trappers. In 1682 LaSalle explored the Mississippi

to its mouth at present-day New Orleans. In 1689, the Iroquois killed

many French settlers at Lachine.

In time, the Native confrontations started to settle. Ìsle d'Orleans

had become less dangerous, and all the sons of Jean Côté, Louis, Martin,

Jean Baptist and Jean Noël took up land there to raise their families.

Québec City now had a several thousand people and likely was not so

desirable a place to live. Stench of human and animal wastes, rats,

chimney smoke, and health problems known to all cities in those days

made country living most attractive.

The oldest Côté boy, Louis, died a young man. His children followed

their mother to the Ìsle aux Coudres. There she was remarried to Guillaume

Lemieux and settled eventually in Saint-Thomas de Montmagny, which

gave rise to the Lemieux dynasty. (Thus it's quite possible that hockey

legend Mario Lemieux has Côté blood.) Martin's sons spent their lives

on the Ìsle d'Orléans and at Beauport while grandson Gabriel settled

at Rimouski. It was this branch of Côtés that produced David Côté

the explorer.

| Paying

homage: Essentially, a peasant meeting with his seigneur

would kneel, remove his hat and sword, and utter an appropriate

oath of allegiance. It was soon clear that picking a day

when the seigneur wasn't home was one way to avoid this belittling

ritual. In New France the practice eventually became redundant

and died out. |

New France and Québec

were starting to take shape. A class structure had begun where educated

people performed management, administrative, and pastoral work; the

uneducated did everything else. The basic difference from other class

structures was that resources here were from the working class. Peasants,

educated or otherwise, realized that the situation in New France was

entirely different from that of the old homeland for several reasons,

perhaps the largest being that Old World system of paying homage and

kow-towing to landholders was no longer part of life in this new land.

In the New

World, workers could survive without the help of a seigneur, since

seigneurity needed them much more than they needed seigneurity. Not

only did farm labourers find that much land was available to them,

but that they were much freer than in the old country and could do

whatever they wanted — including simply disappearing and possibly

working with and for the aboriginals. No matter how lawless, uncivilized,

and unlike Old France, there was always a way to survive and perhaps

even improve their lives.

For those who disliked the drudgery of farm work, it was always possible

to work as an intermediary or broker to deal with Native traders.

Opportunities could be better, sometimes much better, than working

on a seigneurity. As a result, a seigneur's need to keep contented

labourers was resolved by giving them land, or he simply found new

settlers.

Catholic missionaries also found themselves in a much different light

than they'd expected. Priests of the old ilk were revered, so traditionally

the church held a major influence in the life of a peasant labourer.

Since priests were educated, they acted not only for pastoral issues,

but as mediators, negotiators, lawyers, and counsellors, assuring

that parish and church benefitted, and thus adding to their esteem

within the church system.

But the working class started to regard priests differently from the

Old World model since a new set of values had arisen. Churches survived,

but morality and religious values were taking interesting turns. Local

priests realized that the basic French Canadian was highly principled

and independent, while old Catholic icons in Europe began regarding

French Canadians as somewhat immoral and spiritually decrepit.

Varying turns of good seasons, crops, and other successes or failures

left peasant labourers to ponder whether God was important to their

survival after all. What perhaps seemed more important was hard work,

integrity, and resourcefulness. The old system of total religious

dedication and subservience to church and seigneur would never impact

them as it had in France. A change was underway that some believe

formed the cultural basis for New World thinking today. Still many

argue that priests held considerable power and their influence, especially

during elections, is still is an important element in modern-day Québec.

Eventually, and perhaps inevitably, the old systems of seigneurity,

paying homages, fiefdom, and complete subservience to the church and

their masters lost out. Property ownership and self-destiny began

to take root, and life for immigrants in New France steadily gained

favour over life in the old country. While the hard life caused the

return of many people to the old country, for the ancestors of what

was to become French Canada, there was no turning back.

|

The second generation |

| Jean Noël Côté and Helene Graton |

For reasons unknown, this generation mostly used the name Coste and sometimes LeFrise. Surprisingly, children of this generation

would revert to Côté. I was told by one researcher that the

practice of choosing old-country French was common until the late

1700s. While it would literally spell confusion for modern-day researchers,

the fact remains that these names meant the same thing.

Thus the second generation of our branch of Côtés continued with Jean

Noël. In 1673, he married Helene Graton (also spelled Gratton), daughter

of Claude and Marguerite Moncion. Their nine children were:

Louise, 1676-1734

Genevieve, 1679-1706

Jean Baptist, 1682-1712

Pierre, 1684 (died at 10 days old)

Jacques, 1686-1734 (our branch) |

Marie

Charlotte, 1688

(died at 4 months)

Anne, 1690-1743

Joseph, 1692-1737

Augustin, 1695-1737 |

(Joseph and Augustin

appear to have died on the same day. Accident?) All these children

were born on Ìsle d'Orleans in various parish jurisdictions, Ste-Famille,

St-Pierre, and St-Lament. During this time their grandmother Anne

Martin died, specifically in 1684, in Beauport. Both she and her husband

Jean were apparently buried in unmarked graves, although Appendix

1 states otherwise, and in fact their whereabouts are unknown today.

This record in Dreams of Empire-Canada, page 332, from the

Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, 'registre des malades' for the date June 1689,

states:

"helene graton ages de 37 an famme de noil Cottez de La Parou?ge

de St Pierre a Iille dorlean sorte le 12"

... which loosely means Helene Graton, aged 37, wife of Noël Côté?

(note spellings) of (perhaps name of seigneurity) of St. Pierre of

Ìsle de Orleans, departed on the 12th (of June).

A map drawn by Catalogne and Couagne in 1709 at www2.biblinat.gouv.qc.ca/cargeo/htm/a40.htm shows that several Costés had land parcels on Ìsle d'Orleans. It also

states that no more land is available, and thus the next generation

moved on. Today a beautiful farm on the coast, 'the Coterie', property

of Pierre-Célestin Côté located at number 6109 Royal Avenue, testifies

to this.

More interesting

dates:

1706 - Christofori invents the

piano.

1702 to 1713 - Britain wins control

of Acadia (Nova Scotia)

and Newfoundland

in the Queen Anne's War by driving

the French

from Hudson's Bay.

|

|

The third generation |

| Jacques Côté and Madeline Rondeau |

Jacques Côté, from our branch, was the fourth boy. Assuming the homestead

went to the oldest son, he likely had to look elsewhere to settle.

He would have been among the first of the next group of settlers to

choose the Eastern Townships.

Our third generation spread further upstream on the south side of

the St. Lawrence River near the parish of St-Nicolas. While not far

from Québec, this was prime farmland and Jacques' choice of inhabitable

land. On Feb 8, 1706 he married Madeline Rondeau, daughter of Thomas

and Andrée Remondiere in St-Pierre on the island. Then he settled

south of the river at St-Nicolas. Their children, all born at St-Nicolas,

were:

Fabien, 1706-1775

Jacques, 1708-1773 (our branch) |

Louise, 1710-1749

Jean Baptist, 1711-1791 |

Madeline died in 1712,

just six years into the marriage. His oldest child being six and the

youngest barely a year old, Jacques remarried Therese Catherine Lambert

Briene Vincenne. She had seven more children and died in 1730. Apparently

not given to bachelorhood, he remarried yet again in his 46th year

in 1732 to Genevieve Cauchon who bore him no additional children.

Back in 1706 when Jacques was of age to start a family, his father

had been dead for five years and his older brothers had probably taken

over the family homestead. By 1712 all his older brothers had died,

and yet Jacques did not take up the homestead on Ìsle d'Órleans. It's

possible that this land was either assumed by his sister Louise or

given as dowry.

In 1713 the English took total and final control of Nova Scotia, then

Acadia, as one of the settlement terms in the Treaty of Utrecht which ended the War of Spanish Succession. Wars had severely depleted

France and left the colonies economically on their own. England's

takeover of Nova Scotia meant that its inhabitants must pay homage

to the England's royalty and convert to the Protestant Church of England.

This caused a 40-year standoff that ended in 1754 when the governor

of Nova Scotia deported anyone who would not pledge allegiance to

the English Crown.

By 1755, seven to ten thousand French settlers had been deported to

the West Indies, many later settling in the Louisiana territories

where they became what are now known as "Cajuns" (an aberration of

"Canadians"). The harsh treatment they received from the English left

many French Canadians forever embittered about the English Crown.

A few Côtés from other family branches were deported. The bloodline

was over a hundred years in the New World and had already branched

out through three generations. However, the confusion of the time

and the fact that so many perished makes it hard to know exactly who

was involved and their precise lineage. (There is a listing of Cajun

names published showing 88 Costes and 4525 Cotes/Cotoes as descendants

of this epoch.)

At this point, North America was still considered a colony by both

French and English. The French occupied an area extending from the

mouth of the St. Lawrence to the mouth of the Mississippi and west

to the Great Lakes. The English had taken over the American colonies

of the east and the Hudson Bay and west area trading system.

In 1754 a British general named George Washington decided to test

the resolve of the French by attacking a fort on the Monogahela River

near present-day Pittsburgh. Being short on troops and training, his

attack didn't go well. The lesson he learned has stood the test of

time. United States has never attacked the French since and have seldom

considered a fight anywhere unless odds were greatly in their favour.

Thus started the last period of fighting between Britain and France

over French colonies in the New World.

|

The fourth generation |

| Jacques Côté and Marie-Josette Bergeron |

This generation of our ancestors again took land upstream, this time

at Ste-Antoine de Tilly. Like his father, Jacques Côté also

had three marriages. His first produced nine children, his second,

five, and his third in 1756 to Marie-Josette (sometimes "Josephte") Bergeron, daughter

of Jean Baptist Bergeron and Charlotte Houde, produced four children among whom was a son who would ultimately

be our ancestral connection:

Joseph-Jacques-Marie, 1755

Josephte, 1759-1837

|

Marie-Charlotte, 1760-1807

Jean Charles, 1767 - ? (our branch) |

When Jean Charles Côté

was born, his father Jacques was 59 years old, Josette was 45, and

they had been married for 11 years. Interesting!

George Washington's actions in 1754 signalled the start of the Seven

Years War in Europe. Anyone falling asleep in 1754 and waking 25 years

later would have had a huge surprise. The political layout of the

world completely changed. In 1756 war broke out in Europe, and England

used its superior sea power to cut New France off from Europe and

later recapture Québec.

In September of 1759, our branch of the Côtés and a few hundred other

settlers could only watch as 1,200 British soldiers moved into their

town of Ste-Antoine-de-Tilley and took over their church. British

General Wolfe hoped that General Montcalm, who commanded the French

army on the other side of the river, would attack. Montcalm did nothing

and thought that since the cliffs that Québec sat on were said to

be resistant to military attack, he could easily defend the city without

a needless and costly attack on the river or on open land.

What happened next of course is the stuff every Canadian studies in

school: Wolfe mounted an attack from the cliffs, and a battle was

fought on the Plains of Abraham with Montreal falling to the British

in 1760. Wolfe and Montcalm both died in battle. When the smoke cleared,

the debate started over who actually won the war. It would appear

eventually that it was the British. Considering the ages of Jacques

Côté and the rest of his family and their location, it's unlikely

that anyone in this branch was involved in the actual fighting. But

there is no question that they were just across the river, at best,

only a few miles away. The Plains of Abraham were originally the property

of their great-great-great-grandfather.

In 1763, as a result of losing the war, Louis XV of France had the

option to keep Canada or regain the French Caribbean islands taken

by the British four years before (including Guadeloupe and Martinique

and the other minor islands of the French Antilles). His decision

was written into the Treaty of Paris, and from that time forward,

Canada, excepting the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon that were

kept by France to provide a settlement for fishermen from old France,

became a property of the British Commonwealth. Aside from climate,

Canada and its potential wealth was less desirable to Louis XV than

a few scantily inhabited Caribbean islands. One perhaps wonders about

his sanity.

The French regime was officially over. The largest and longest period

of French emigration to the New World ended. The relationship between

France and Québec would be forever tarnished, possibly even severed.

Earlier ineptitude, neglect, and insufficient support could be forgiven.

For anyone who ever wondered why French Canada seemed to have congenital

animosity to old France, being squandered for a few Caribbean islands

might have had something to do with it.

In 1764, British general James Murray was appointed to transform the

colony, unbelievably, into an English colony. Since he had 1,500 soldiers

and there were 70,000 French Canadians, he realized that a takeover

similar to that in Nova Scotia might not be easy and could cause yet

another revolution. He decided against it.

By 1766 Murray hadn't produced the results expected, and he was replaced

by Sir Guy Carleton. On looking over the situation, Carleton decided

that Murray's actions were reasonable, and he proposed that French

Canada be allowed to have its own language, church, justice system,

and so on.

While Britain contemplated this, the Boston Tea Party (1773) and the

American War of Independence separated United States from England.

40,000 loyalists fled to Canada from the American colonies thus starting

the English-speaking settlements of New Brunswick and Western Québec

(later Ontario).

In 1774 the British, pressured by their problems in the US and remembering

the debacle in the takeover of Nova Scotia, passed the Québec Act which recognized territorial French legal codes and land-tenure system

and granted legal status to the Roman Catholic church. Clearly their

takeover of Québec would go a lot differently than that of Nova Scotia

or of the American states.

In 1783, the American Revolution created a border between Canada and

the US to the Great Lakes.

The French Revolution, starting in 1789 and ending with the beheading

of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in 1793, ended the French royal

dynasties with an invention created and named for Dr. Guillotine.

France was weakened and bankrupt, and its troubles were really just

beginning. England declared war again over the king's beheading, and

the next generation would experience Robespierre and Napoleon. In

the wake of all this, France would never again be a world power.

|

The fifth generation |

| Jean Charles Côté and Pelagie Croteau |

When Jean Charles Côté was marriageable, Québec was officially under

the control of the British Commonwealth, but in reality, not much

had changed from the prior generation. In 1788, the church at Ste-Antoine

de Tilly burned down and a new one was built. In 1791, the Constitutional

Act separated Québec into Upper (Ontario) and Lower (Québec).

It was during that year Jean Charles married Pelagie Croteau, daughter

of Louis Francois and Felicite Chaine. There were five children before her death in 1811:

Jean Baptist, 1792 - ?

Francois Xavier, 1793 (our branch)

Flavie, 1798-1868 |

Francois, 1800 - ?

Cecile Angele, 1807 - ? |

No official record is

yet found of their birth dates, but it appears that they were all

born in Ste-Antoine de Tilly, Québec. Apparently widowed, Jean Charles remarried

in 1816 to Marie Marotteand had another daughter, Adelaide, from this marriage.

In 1803, France, did a land deal called the Louisiana Purchase and

sold all lands west of the Mississippi to the Rockies and south of

Québec to the Gulf of Mexico for $15 million.

Again, war intervened before the next generation could develop, specifically

the War of 1812. Here the US declared war on Canada hoping to liberate

it from the British. Britain sent many soldiers to help the colonies

fight the Americans. In the end, not much was lost or gained other

than Toronto was temporarily under American control and a British

military unit got close enough to the US president's residence in

Washington to set fire to it. (It was then painted white, and the White

House has been white ever since.)

In 1818, two totally unrelated events occurred that affect us to this

very day:

The 49th parallel was accepted as the division between British and

American possessions in North America, and the Christmas carol Silent

Night was written. It may be surprising that Huron Carol, mentioned above, is about twice as old as Silent Night. (Huron Carol is over 350 years old, while Silent Night is less

than 200.)

|

The sixth generation |

| Francois Xavier Côté and Rosalie Rose Morin |

Our sixth generation descended from Francois Xavier who married Angelique

Bedard, daughter of Jean Baptist and Elisabeth AuClair in 1820. That

marriage produced six offspring before Angelique's early death. Francois

Xavier remarried in 1826 to Rosalie Rose Morin (sometimes called

Marion). It appears that the family moved to St-Flavien, Québec and had two

more children:

| Louis, b/d unknown |

Francois, 1820-1902 (our branch) |

Records were not well

kept, and there are considerable date conflicts. St-Flavien is about

20 miles south of Ste-Antoine de Tilly.

This was another period when many Côtés as well as other French Canadian

families migrated to other parts of North America. The area that included

the Eastern Townships was cleared and developed to the extent that

it is today, and there was little land to be had for this generation.

In the 1830s, a serious economic depression together with severe overpopulation

in the Eastern Townships created enormous hardships to the point that

there were minor revolts and concerns about political upheaval.

Most Côtés living today in Maine, Vermont, New York, and even California,

emigrated from French-Canadian settlements during this time.

From 1815 to 1855, the British actively encouraged British immigration,

and one million Britons moved into the Canadian Territories.

In the 1840s a potato famine in Ireland created wave after wave of

"coffin ships" that is, ships having people and families on board

sick with typhus, starving, or dead. Many Irish names in Québec can

be traced to this origin. See www.ncf.carleton.ca/~cd200/mac36.html and www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/famine.

|

The seventh generation |

| Francois Côté and Desanges Chaurette |

Our seventh generation is from Francois who married Desanges Chaurette

(sometimes Choret), daughter of Joseph and Marguerite Aubin, in 1845.

While they were both born in St-Flavien, they were married in Ste-Antoine

de Tilley in 1845. Their children, also born in St-Flavien are:

Philomene,

1847

Honore, 1849

Lazare, 1850-1914 (our branch)

Marie, 1852 |

Michel, 1853-1935

Malvina, 1856

Elize, 1858

Zelire, 1860 |

In approximately 1863,

they migrated to Benson in Swift County, Minnesota in the United States

without the older boys Honore and Lazare who were 26 and 25 respectively.

Today it might seem an unpatriotic gesture to move to the US. But in those years the border seemed fairly insignificant and people often relocated without bureaucratic fuss wherever economic conditions led them. Once there, they had two more children, Alphonse in 1863 and Clarisse

in 1864.

In this period, two events occurred having great impact in North America:

The American Civil War started in 1863; and the British territories,

Québec, Ontario, and Nova Scotia accepted confederation which led to the creation of the Dominion

of Canada in 1867. In 1870 Louis Riel led the Metis resisting

Canada's authority in the west by seizing Fort Garry at Winnipeg and

presenting demands for rights for the Metis in the northwest. In 1870

Manitoba became a province based on those demands, and Riel fled to

the US.

|

The eighth generation |

| Lazare Côté and Clarisse Bergeron |

The eighth and final generation of Côtés, as they relate to my Thiévin

family, began when Lazare Côté married Clarisse Bergeron in 1870 in

St-Flavien, Québec. Their daughter Marie-Louise would become our matriarch,

and after her marriage, she became the final Côté in our lineage.

Her parents could hardly be accused of mediocrity with 14 children:

Mary,

1871

Annie, 1872

Jamie, 1874

William, 1876

Albert, 1877

Onesime (Pete), 1879

John, 1881 |

Alfred,

1883

Zenaide, 1885

Mathias, 1887

Melvina, 1889

Marie-Louise, 1891 (our branch)

Ulric, 1892

Clarisse, 1894 |

In 1877, Lazare and

his family made a journey already made by his parents to Minnesota where they could get homesteading land. For unknown reasons, Lazare and Clarisse made the decision to move on, this time to Olga, North Dakota, where Marie-Louise and Ulric were born in 1891 and 1892 respectively. Finally they settled

in Wales, North Dakota where they had their final child, Clarisse, in 1894.

Lazare, like his ancestors, was a farmer and labourer, and there was

little work or large enough farms in North Dakota. In 1900, upon hearing

there were Western Canadian homesteads available, he decided to look further.

Having moved too many times before, his wife Clarisse initially

stayed in North Dakota. While the 49th parallel was the border, Lazare's

Canadian citizenship made it a simple matter when he chose to settle in 1902 near "Alma" Post

Office a few miles from present day Forget, Saskatchewan.

Alma Post Office, located on section 24, township 8, range 7, west of the

2nd meridian, was then in the Assiniboine Territory of the North West

Territories, and in 1905 this area became Saskatchewan, a province

of Canada. Alma P.O. closed in 1905 after the railway went through

a few miles away and the Forget post office opened. This sometimes

confusing name came from Amedee-Emmanuel Forget who was the last lieutenant

governor of the Assiniboine [Northwest] Territories. (Almost any level

internet search for Forget returns references to the Roman Catholic

convent that became a landmark there. I, my two immediate brothers,

and several first cousins attended this convent for the first years

of our schooling in the 1950s.)

At $10 each, Lazare and his boys each bought a homestead for a total

of seven. Since Clarisse disliked sod houses, they built a log house

and essentially started farming in the same way as thousands of others

who arrived on the prairies in those times. Lazare died in 1914, Clarisse

in 1921, and they were buried at the cemetery in Lampman, Saskatchewan.

|

The ninth generation |

| Marie-Louise Côté and Louis Thiévin |

Marie-Louise Côté's marriage in 1909 led to a ninth

generation of Jean Côté albeit with my family name, that is, Thiévin. Louis was born

in Pannece in Brittany, France, the son of Pierre Thiévin and

Marie Gougeon. The family had immigrated to Canada when Louis was

a toddler, arriving in Grande Clairière, Manitoba in 1889. After living

there four years and acquiring some cattle, they moved with their

eight children and livestock by ox-drawn cart to Alma Post Office. It was here that young Louis met

his bride, Marie-Louise. They would settle in Saskatchewan south of

Forget near the towns of Benson and Lampman, and not to break traditions of having large families,

the fruits of their marriage were 13 children:

Albert,

1910

Annie, 1911

Blanche, 1913

Elizabeth, 1914

Roger, 1916

Alphonse, 1918

Marie, 1921 |

Aime,

1923 (my family branch)

Rita, 1925

Alice, 1927

Helene, 1929

Paul, 1931

Celine, 1933 |

Louis Thiévin was an

excellent carpenter and farmed near Benson. He retired in Benson and

died after a struggle with lung cancer at Estevan in 1958. Louise-Marie

died in Estevan in 1974. These were two of the nicest of people ever

put on the planet. I have several memories.

Since Grandma disapproved of alcohol, Grandpa would take guests out

to his workshop. There, hidden away, were the libations they sought, and

for as long as I remember, he never was without. I also remember Grandma

tripping people as they went in and out of the kitchen at the New

Year's Day celebration that they always held at their home. Possibly

she also liked to drink a bit, but would never, ever let it be known.

Both were hard-working and fun-loving people who will always be remembered.

|

|

| Marie-Louise Côté at 17 (1908), the year before her marriage to Louis

Thiévin. |

Louis

Thiévin and Côté in-laws: At the centre of this photo

is Louis, and immediately below him and to our left is Marie-Louise

Côté holding, presumably, their first born, Albert Thiévin. |

|

The tenth and subsequent generations |

| (offspring of Marie-Louise Côté with non-Côté surnames) |

My siblings and I, born in the 1950s and 60s, represent the tenth generation of Jean Côté since

his arrival in Canada nearly 400 years ago. By 2003, 14 or more generations that led to our specific family had been propagated. In truth, however, it's possible that other children of Jean Côté propagated even more generations. The long and winding roads that led Jean Côté's other children into the 21st century might well differ, but we will probably never know who they are or what role they play in the Côté mosaic. The research on these pages, of course, focuses only on the Côté descendants who led to my immediate family.

There has been a dramatic difference in the rate of proliferation in modern times. Consider this:

From 1604 (Jean's birth) to 1891 (Marie-Louise's birth), 287 years

and eight generations transpired, averaging 36 years per generation.

But grandmother Marie-Louise's offspring produced a whopping five generations

between 1913 and 2002, averaging fewer than 18 years per generation

— clearly double the rate.

Obviously Marie-Louise's offspring bear as much Côté blood as descendants

who still bear the name. The first of these, generation 9, are each

of her immediate, surviving children, the first two dying from pneumonia

on the harsh prairies. She would eventually have 64 grandchildren

(generation 10), and 187 great-grandchildren (generation 11), before

her death in 1975. Since then, at least three more generations have emerged.

My father Aime was among Marie-Louise's many children in the ninth

generation. He married Bernadette Dubreuil in 1945, daughter of Francois Dubreuil

and Rose Montes. Their children were me (Tom), Richard, Denis,

Jim, Charlotte, Francis, Marie, Dianne, Marcel, and Jacqueline.

My father served his country in World War II with the Royal Canadian

Air Force. He was a wireless operator and flew 28 operations before

returning in 1945 to marry Bernadette. He farmed and then ran a garage

business in Estevan called Aime's Hillside Service. When his own interest

in this waned, he purchased a small resort at Round Lake in the Qu'Appelle

Valley called Maple Grove Resort. Both were eventually sold to interests

outside the family. Dad was an excellent hunter and trapper, a farmer,

mechanic, and businessman. He liked to think of himself as a jack

of all trades and master of none, but he was clearly made of survival

instincts handed down to him by parents who taught their children

to take nothing for granted.

Other Côtés (who emigrated from France but weren't related to Jean)

Tanguay (a French Compendium of French Canadian Settlers) mentions

three or four different Côtés coming from France in the 1700 and 1800

centuries. Jean, or Jehan as he was known, was the earliest of all.

He was the ancestor of the majority, if not of all the Côtés whose

roots in North America go back three centuries and more.

Jean had been dead several years when Abraham Côté (or Botte) dit

Soraká arrived from Dieppe. Abraham was married at the Mountain Indian

Mission at Montreal on 14 October 1750 to the Onondaga Marie Aéndea.

This man, who may not even have been a Côté (it might have been a

dit name) since his children were baptized under the name of Bote

or Soraká, left no known descendants apart from his own offspring.

It is possible that they assimilated into the aboriginal culture and

lost their real name.

In the following century other Côtés appeared: Claude, a native of

Lyon, married Françoise-Angélique Pampalon in Québec on 20 July 1724

and remarried there on 20 June 1728 to Marie-Genevieve Baudouin. He

had at least 13 children; two of his sons had wives.

Finally, there is another Jean Côté, this one from Languedoc, who

probably arrived at the end of the French regime. This Jean married

Marie-Francoise Lefebvre at Saint-Constant on 6 June 1768.

In fact, the Côté name had the potential to have also been a dit name.

For example, it would have been possible in French Canada to have

the name added to the original name if that person in some way had

a characteristic that led to an intuitive meaning. Thus Jean Doe

could have become Jean Doe dit Côté since Côté means 'side'

or 'coast' (as in coastline) if he lived beside something significant

such as the St. Lawrence or the Bay of Fundy. To take this supposition

further, eventually the Côté name might have stuck and a land title

or church record might have simply listed him as Jean Côté, leaving

out the real name entirely. This process happened often and

is the kind of thing that makes careful genealogical study necessary.

The Indian or Metis connection:

Many of our relatives have wondered about the possibility of aboriginal

blood and how much of it might run in our veins. This is not an easy

question to explore, and the answer might never be known.

There's much to ponder: In terms of lineage, it appears there is no

formal, documented intermarriage with non- French-Canadian Europeans

throughout our branch of Côtés (emphasis on our branch). Granted, this

depends on documents that genealogists often consider less than ideal

data sources.

Since our branch of Côtés were essentially farmers and land settlers,

not soldiers, trappers, or traders, their exposure to Natives was

considerably less than for other occupations after the first generations.

And since our branch lived in eastern townships south of the St. Lawrence

River, they were quite apart from interactivity with the Iroquois

in early years on the north side of the river.

| (photos coming soon ...) |